|

| USS Yorktown under attack during the Battle of Midway |

Today is the 70th anniversary of the first and most critical day of the Battle of Midway.

On the one hand, the battle is among the best remembered of the war because of its obvious importance and the high drama of the situation and how it played out. You had an enormous Japanese fleet, heretofore highly successful, being defeated in the most dramatic fashion possible by the outnumbered, plucky Ameircans.

that's certainly the popular image anyway, as shown by Hollywood in the movie Midway and in popular books such as Incredible Victory and Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan.

Of course more recent scholarship, most vividly in Shattered Sword, shows that it wasn't quite as one-sided a situation as all that and that the odds were not as much against the United States as the raw numbers might suggest.

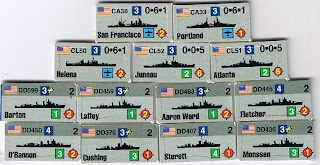

This is no news to wargamers, of course. Midway is one of the original, classic wargame situations in the hobby, ever since the seminal Avalon Hill game Midway appeared in 1964. The appeal of Midway, from a wargaming standpoint, is that it's not only an important battle, but a remarkable even one. Yes, the Japanese had a large fleet, but at the critical point the two sides were very comparable in strength. The Japanese carrier task force was comprised of four fleet carriers carrying 225 aircraft escorted by five battleships and cruisers while the American task force was comprised of three fleet carriers with 233 aircraft and an escort including eight cruisers. The island of Midway formed a fourth "aircraft carrier" with another 81 combat aircraft.

Each side had advantages. For the Japanese this included highly trained and experienced aircrew with first-rate planes using advanced carrier doctrine and techniques. For the Americans there was the advantage of code-breaking and superior damage control. While the Japanese held an advantage in plane quality generally, the American Wildcats were learning to hold their own against the Zero and the Dauntless Divebombers were excellent.

Perhaps nothing helped the Americans more than their good luck and some good leadership. The key decision by Wade McClusky leading the Enterprise divebombers to follow an errant Japanese destroyer to the carriers and the fortuitous timing of the various uncoordinated American attacks created the conditions for victory.

But no one can read the details of how this all happened without seeing that it could very easily have turned out the other way. The Hornet divebombers strike, for example, completely missed the Japanese fleet and ended up landing on midway. If the Enterprise strike had done likewise then only the Yorktown's strike would have ended up finding the Japanese fleet. That attack sunk the Kaga. Historically the counterstrike by the Hiryu was enough to sink the Yorktown, but what would have happened if there had been three surviving Japanese carriers available to launch? We can't know for sure, of course, but Capt. Wayne Hughes analysis in the book Fleet Tactics suggests that under the conditions of 1942 carrier battles each carrier deck load could be expected to sink or disable one opposing carrier on average. So it's quite likely that the US might have lost all three of the Yorktown class ships on the afternoon of June 4th.

Midway itself probably would not have fallen, as the projected Japanese invasion force seems wholly inadequate to defeat the marines present on the base, but the Japanese would have been well-placed to follow up their success. Certainly there would have been no Guadalcanal campaign as the United States would have had to husband its remaining carrier assets (primarily the Saratoga and the Wasp) until the Essex class ships started to arrive.

The Japanese naval aviation would also have been in much better shape as there would have been no heavy attrition in the Solomons and the carrier pilots would have been kept aboard their carriers.

As to whether the Japanese would have ultimately prevailed, it's hard to say. They still had to cope with the fact that their industrial strength was inadequate to compete with America over the long haul, but they would have had many opportunities to make the long and challenging drive across there Pacific and even longer and more challenging affair -- at least until the atom bomb weighed in.

For me, personally, Midway has always been one of my favorite topics in wargaming. My very first wargame was Avalon Hill's Midway, which I still think is one of the best classic wargames. I also have a half-dozen other Midway wargames as well.